Driving while listening to a podcast. Cleaning the apartment while talking on the phone.

To make better use of our seemingly shrinking time, we often try to do multiple things at once. But is that really beneficial—or perhaps even harmful at the end of the day?

On a physical level, multitasking does work—drummers are a great example: they play different parts of the instrument simultaneously with both hands and feet. But things look different when it comes to thinking. On a cognitive level, multitasking is not actually possible. What we experience as “doing things at the same time” is in reality the brain constantly switching between tasks, a process known as task switching.

Is multitasking bad?

In short: yes, at least for cognitive tasks. Multiple studies [1] [2] have shown that multitasking:

- makes tasks take longer

- increases the number of errors

- raises energy consumption due to constant switching

In other words, you unnecessarily wear yourself out. And there’s more: those who constantly multitask are training their brains to react quickly rather than think deeply. If you're managing multiple projects at once, it takes longer to complete them because each one comes with its own mental overhead.

That’s why Cal Newport, author of Deep Work and Slow Productivity, advocates for keeping the number of concurrent projects as low as possible.

Why is it so hard to focus on just one thing?

Because we’ve trained ourselves for years to do multiple things at once. Whether to feel more productive (“I got so much done”) or to gain social recognition (“I can handle a lot”), multitasking often looks impressive. It makes us seem active, effective, successful.

In contrast, monotasking often seems unspectacular. And in all of this, the smartphone is our biggest enemy. How often do we have it lying right next to us—on the desk, on the couch—and glance at it again and again for the next dopamine kick?

Isn’t monotasking inefficient in a fast-paced world?

Actually, monotasking gets things done faster. It makes sense: if you only do one thing, you don’t get lost in others. Focusing on a single task reduces mistakes and improves the quality of the outcome.

What are the negative effects of constant multitasking?

Over time, multitasking can overload your nervous system, leading to:

- inner restlessness

- a higher stress level

- a constant feeling of being overwhelmed

Typical consequences:

- - Reduced productivity

- - Higher stress

- - Less focus: wandering thoughts

- - A sense of inner tension and time pressure

How can I tell I’m multitasking?

Simple: you’ve lost focus on your original task and got distracted. A few examples:

- Glancing at your phone while creating a presentation on your computer

- Working while listening to a podcast

- Answering emails while talking on the phone

- Being in a conversation but mentally somewhere else

- Constantly jumping between tasks

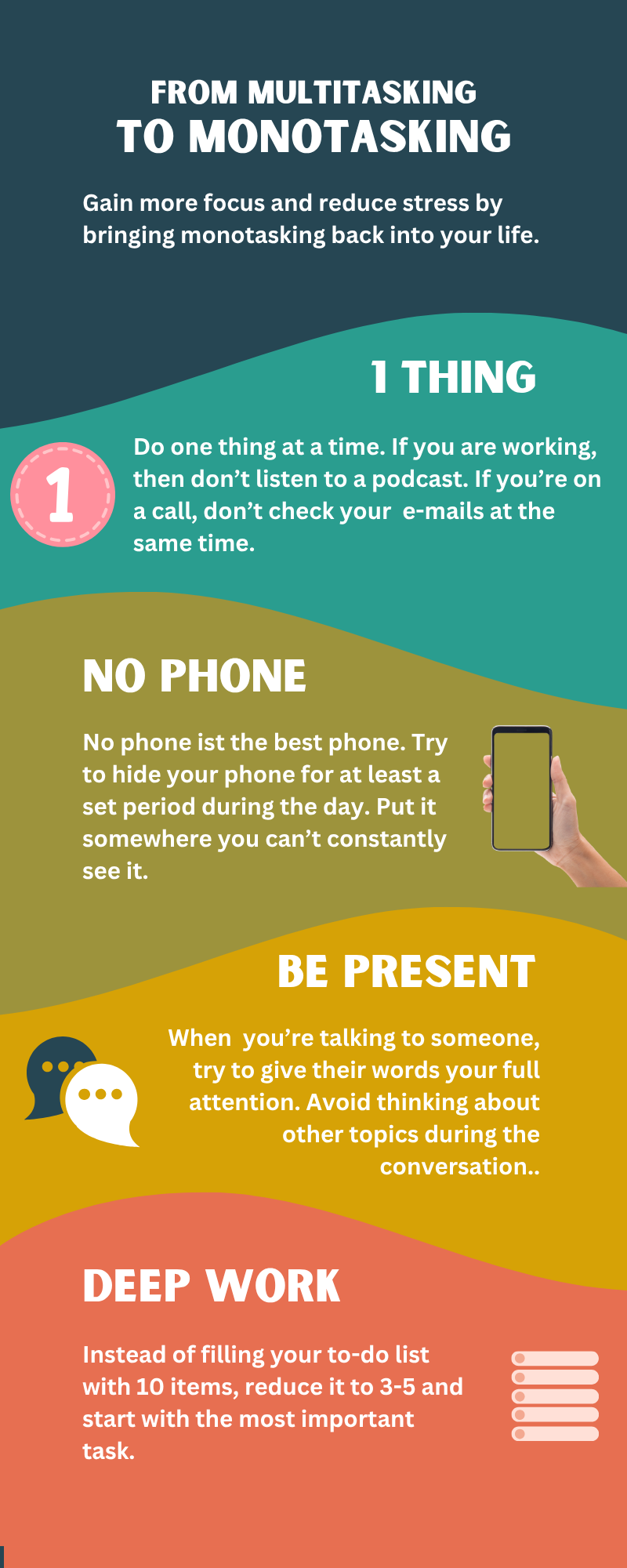

How can I switch to monotasking?

Just like you trained yourself to multitask, you can unlearn it too—like a muscle you build. Start with small experiments, without putting pressure on yourself:

1. Put your smartphone away!

Get into the habit of placing your phone out of sight. Put it behind you, not in front of you on the desk. In the evening, leave it in another room—even just for half an hour. Every visual contact with your phone triggers a mental impulse.

2. The “One Thing at a Time” Rule

For the next hour, tell yourself: “I will do only ONE thing.” Whether it’s working on a document, reading a book, or cleaning—stay present with that task.

3. Digital cleanup

Close all unnecessary tabs and apps.

4. Set specific time blocks

Use techniques like the Pomodoro method (25 minutes focus, 5 minutes break) or 90-minute deep work sessions with a clear start and end.

5. Mini mindfulness check-ins

Ask yourself regularly: “Am I truly focused on what I’m doing right now?” If not, take a deep breath and gently bring your attention back to the task—no self-judgment, just awareness.

6. Plan less, dive deeper

Instead of putting ten tasks on your to-do list, choose just three priorities for the day— and start with the most important one.

Sources:

[1] https://news.stanford.edu/stories/2009/08/multitask-research-study-082409